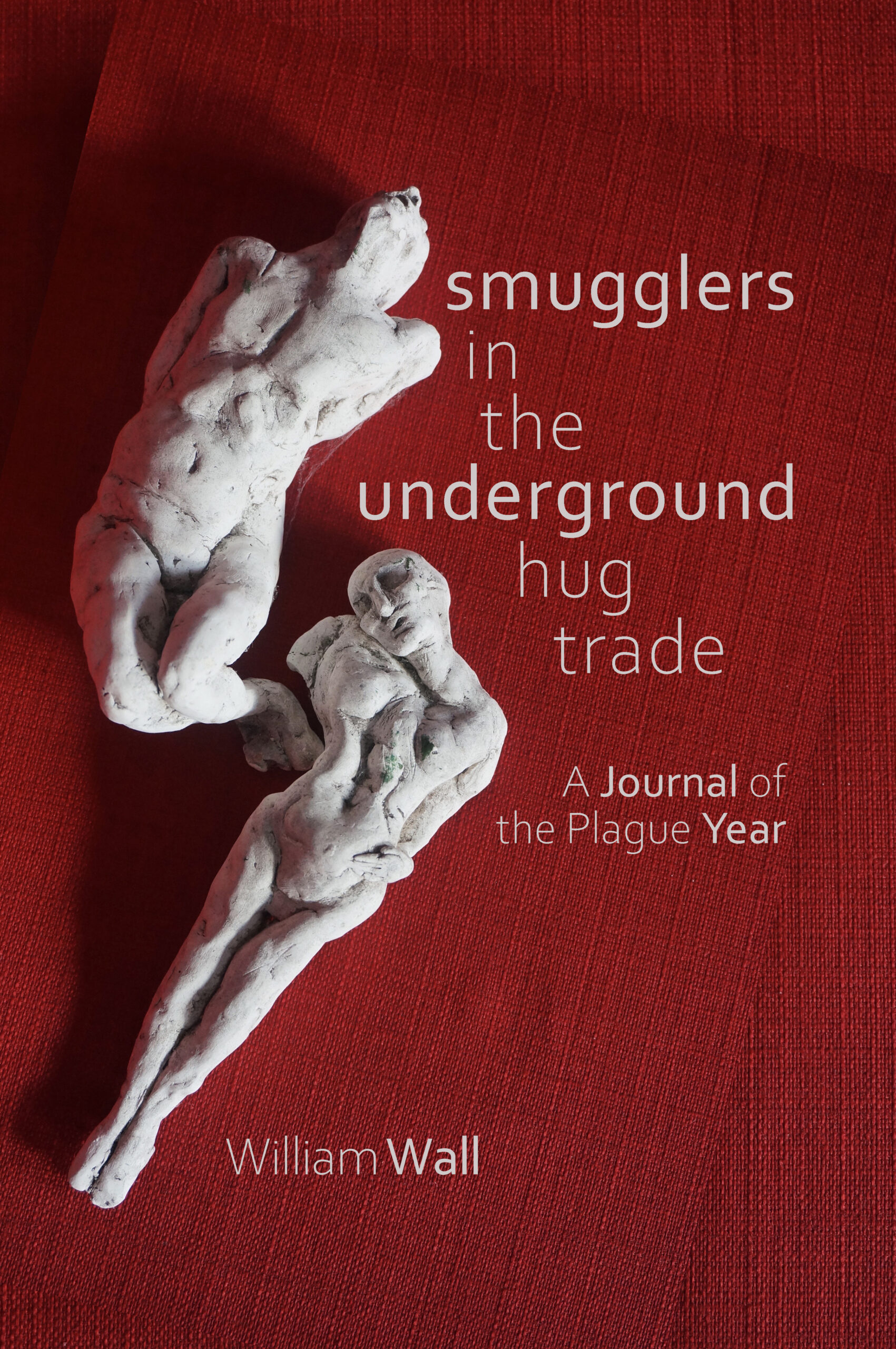

Smugglers In The UnderGround Hug Trade

Poetry (Doire Press, Galway, 2021)

Click on the image to be taken to the publisher’s page or to buy the book.

“No longer were there individual destinies; only a collective destiny, made of plague.” William Wall quotes astutely from Camus in his contemporaneous journal of the pandemic. Set between Cork and Camogli, these poems record 2020’s horrors, governmental failings and unexpected kindnesses. Nature becomes compromised – at one outdoor birthday gathering, we “turn away / in case the spring breeze / carries contagion” – though we are reminded also of how “people sang opera / balcony to balcony”. The titular phrase is taken from Wall’s poignant vision of a world where “no one will ever be isolated / in our intensive care”. For those struggling to process the last year, this journal is testament to human connection through generosity and shared experience, as well as through the virus. Tanvi Roberts

Read a poem from the collection

In time of quarantine

and some of us will be smugglers

in the underground hug trade

black market kissers

purveyors of under-the-counter embraces

solicitors of indulgence

intimacy pushers on the bright side of the street

our only law will be affection

our currency will be love

from which there is no default

you will find us in the missing places

in the spaces between stony stares

in hospitable infirmaries

loitering by the private doors of public houses

holding hands like young lovers on a first night out

returning advances

transported by proximity

no one will ever be isolated

in our intensive care

April 27th

Read a poem from the collection

In the declining evening I swim

i

in the declining evening I swim

wind over sand erasing the sea’s staves

the ticking tide

in the limestone breakwater

bottles of Pepsi pieces of plastic can-rings net

in his sixty-fifth year my father

was already old

his ruined back

his big rough farmer hands softening to wax

and here I am at the same age

entering the same sea at the same time of evening

gingerly stepping on the thin line of gravel at the edge

a golden sea

the island and its light on the pencil-line of horizon

on either side the villages falling slowly into the sand

in the struggle between land and sea

better to back the water

it wears the world away like time

the swollen belly of a spring tide

brings forth monsters

the eyes of a lonely child

a crippled boy

a drowned sailor

an old man with the big sad eyes of a seal

and swimming in the sloe-blue sea

contained in my own broken breathing

never stirring the surface tension

the spiritous membrane

half sea half bone I am shedding

the shoreline like an old shell

and from here the world

looks like a pleasure ground

for some rapacious species

not recognisably anyone I know

ii

a girl in wheelchair

stares hungrily at the sea

when I pass

at a safe distance

she does not break her gaze

a history of what will never be

iii

there are jellyfish

as clear as water

they wash up at our feet

visible only as a shift of light

and a shape not made of sand

two young girls have

forgotten to rescue their dolls

they float on the evening tide

their long hair flowing

like plastic Ophelias

once upon a time

the dolls could just be dolls

but in the seas off Lampedusa

and the beaches of Lesbos

our fearful innocence went down

at the water’s edge

two girls dancing a slip jig

their reflection in the wet sand

is two crows fighting

July 25th

Julian Girdham's review of Smugglers

I really have no enthusiasm for reading a ‘pandemic novel.’ Most of us have had quite enough reading about ‘it’ over the last 18 months, and a pleasure has been to turn off the news and fold the paper, and turn to novels set in early 1930s England, or early 20th century German East Africa, or New Ross in the 1980s, and lose ourselves in other worlds (though Hamnet was a bit too close to the bone).

However, I did find myself buying, reading and enjoying William Wall’s Smugglers in the Underground Hug Trade: a journal of the plague year (attractively produced by Doire Press). It is a sequence of poems set in 2020, describing and reflecting on the author’s life in the first year of the pandemic. Each poem is dated (some, like one on Trump visiting the CDC, reminded me a little of Nick Asbury’s poetic responses in his Realtime Notes). The lines are unpunctuated, note-like at times, almost jottings. The range is wide: there is anger here, and anxiety, but also an appreciation of beauty, and the underlying love story of Wall’s companionship with his wife (we survive by loving / one morsel at a time: the ‘we’ of them as a couple sometimes feeling like the ‘we’ of all our experiences). He puts our experience in the context of other plagues, referencing Defoe (as in the sub-title, of course), Camus, Pepys, Thucydides, Manzoni, Dante Alighieri and Boccaccio.

Things Italian appear throughout the sequence. In the second poem, ‘Porto Corsini’, Wall is in pre-panic Liguria:

from the pier at Porto Corsini

we leave the open sea

a voyage to the interior

that weaves a gleaming

basketwork of memory

and forgetting

But by February 24th (‘La Quarantena’) the virus has come uncomfortably close, and he thinks of Florence in 1630:

they traced the chicken vendor

and his family

they traced his contacts

they closed the border

and still it came

the plague is out

no holding it now

By February 26th in ‘Flight to Ireland’ we are fleeing the epidemic via a deserted Fiumicino Airport in Rome, and the rest of the book is set in County Cork. Like everyone else in those early months, Wall takes consolation from small things, especially the natural world. The sea (and the local beach) is a strong, and comforting, presence throughout (‘The Receiver of Wreck’, ‘In the Declining Evening I Swim’, ‘You Walk Away – on the lifting of lockdown’, ‘We read The Inferno at the Beach’, ‘Even the Orcas’ among other poems), though there are darker connotations of water too (the successive waves in the strangest year we have lived; his body being the shipwreck of bones; the virus being a floating mine /drifting among shipwrecked souls).

By December 2020, and the final pages of the book, Wall has been through the ups and downs everyone else experienced. On December 5th there is a lovely poem called ‘The Jewish Cemetery’ about the late David Marcus, who I once spent time with at the Irish Press offices in Burgh Quay (he was kind and perceptive about a story written by a callow young man). In ‘Christmas’ the day

dawns bright

all the open doors

memory in the mist

over the valley

here’s to absent friends

There is ease and libation as four glasses of wine are poured. And now here we are, at the end of 2021, facing another uncertain Christmas, and we will treasure simple things, and family, and friends, and libation.

On December 31st he ends with ‘O You Who Come to This House of Pain’, with its refrain watch whom you trust and how you go / these are the dark days. But there is a final hopeful note, quoting Camus:

Finally, in the depth of winter I learned that there was in me an invincible summer.

and in the final sentence of the Notes which follow the poems he writes that hope for the future lies in the vaccine.

As we now know, there was much more to come, but his book is done. It would be hard to imagine a 2021 version: is there more to say? For how long can poetry respond directly to this event without burning out?

On December 5th, in the poignant ‘In Memoriam’ he thinks of the death of a middle-aged hairdresser:

but you went to get your hair cut

and his daughter told you the news

he used to say your hair was beautiful

he understood its fall

at the scale of the everyday

these things are colossal.

Just so: what we have experienced has felt colossal at the scale of the everyday, and Wall has given us a memorable record of just what that has been like.

The Year That Never Happened – My essay about writing Smugglers

When my wife Liz came to photograph the cover image for Smugglers In the Underground Hug Trade we decided it would be a good thing to contact the artist who made the figures, whom we had not met in perhaps 30 years. Her name was Breda Lynch and when we made contact through a mutual acquaintance we were shocked and profoundly moved to hear from her husband that she had died of Covid only a few months before. Somehow, that simple, even brutal fact, came to symbolise the whole project for us.

The book, in fact had been Liz’s idea. We were walking Ardnahinch Strand in east Cork one morning of bitter easterly wind, in the days before the first lockdown, and discussing the fact that we had been able to find so little direct writing on plagues and pandemics. We knew our Boccaccio, of course, and Manzoni’s The Betrothed has a superb description of the plague in Milan. Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year (which gives my book its subtitle) is an equally well-researched account, but it must be observed that neither Manzoni nor Defoe actually lived through the events they describe in any meaningful sense – Defoe was five when it broke out and Manzoni was writing hundreds of years after the events described in his book.

Precious little, it seems, is written during human catastrophes. This is not a surprise. I know of only two songs that might be contemporaneous with the Great Famine – The Praties They Grow Small and Na Prátaí Dubha. There are very few substantial direct accounts in English literature of the Spanish Flu of 1918-1919 – Virginia Woolf survived the infection and many scholars believe her Mrs Dalloway is a survivor. Then there’s William Maxwell’s beautiful They Came Like Swallows and Katherine Ann Porter’s Pale Horse, Pale Rider – Porter herself barely survived the infection and certainly suffered from what we would now call long flu.

It’s possible that Yeats’s The Second Coming takes its apocalyptic imagery from the pandemic (as eloquently described by Daniel Mulhall in this paper) and there is a sprinkling of poems or parts of poems by various contemporaries, and that’s it. Out of the thousands of books in English that were written during and immediately after the epidemic by people who survived it, we have a handful of texts which reference it directly.

Perhaps the enormity of the cataclysm chokes creativity. I have certainly heard many fellow writers complaining that they were unable to write during lockdown.

In my case I can say that Liz urged me to document the experience. At first I tried a prose journal but quickly realised that poetry was the only way I could encapsulate the random and fragmentary experiences – the silence, the news, the rumours, the hopes, the stories of friends and neighbours, the steady stream of reliable science, the charlatans peddling fake cures, the presidents and prime ministers, the bleach, the masks, the hand-washing, the lockdowns and releases and the numbers, always the numbers. I tried to write something every day. Sometimes it was a line or two, sometimes a whole poem. Gradually the poems began to take shape.

Themes began to emerge – silence, birdsong, enclosure and escape, time, history, numbers, mortality on the personal and the statistical scale, hope and despair, love and the importance of family. My reading found its way into what was becoming a collection rather than just a diary – Thucydides who gave us the first account of a plague (in Athens in 430BC), Boccaccio and Defoe and Manzoni and the others, but also Dante (the 700th anniversary of whose death falls this year) and Camus – although Camus’ plague is really fascism – and many others. I decided to limit the journal to that first year, 2020. I don’t think I could have continued anyway – I found the process emotionally exhausting.

My connection with Italy made the situation there particularly affecting for me. Liz and I were in Liguria when the epidemic broke out. We left in a hurry because we could see that it was going to be bad – though we could not have foreseen quite how bad – and we thought it best to be at home. As it happens, not long after we left Italians were literally confined to their homes. The images from Bergamo shocked the world and woke us up to just how terrible a global pandemic is.

But travelling south in an empty train that morning in February, through empty stations and later through an almost empty airport was one of the strangest experiences of our lives. We spent a day in Rome in a friend’s house before catching our flight and I have an acute memory of walking into Piazza di Spagna, normally crowded with tourists, and encountering a handful of people and a couple of policemen. The eeriness of the empty city.

Back in Ireland I found reading about plagues strangely comforting. Boccaccio taught me that we must laugh, Manzoni that we must love, but also that we must ignore the charlatans including those who suggest that prayer is the best prophylactic against Covid. When I hear an American Republican declaring that he will trust in Jesus to protect against the disease, I think of Manzoni and the parades of saint’s relics through the city of Milan that actually spread the disease wherever they went. Florence, as I discovered from a brilliant history of the period, John Henderson’s Florence Under Siege (Yale University Press), took a more scientific approach and suffered a fraction of the casualties. Plagues come and go, the history taught me, and we survive and make a new way of living which becomes normality and which has its compensations and its pleasures.

When I think back over 2020 now, one of the most striking memories is of the prevalence in the media of serious, authoritative scientific voices – the doctors, the virologists, the statisticians, the epidemiologists and the medical historians. Outstanding was our team of public health specialists among whom Dr Tony Holohan has a deservedly heroic status. Then there were the doctors and nurses and medical staff in general whose struggle with the epidemic was seemingly endless and exhausting but who never wavered in our defence.

By contrast, the petty whingeing of the anti-maskers and no-vaxxers seems like the annoying buzz of a bluebottle in a bedroom during a sleepless. night. They talked of liberty as though liberty trumped solidarity. In reality what they were vaunting was selfishness, not freedom.

Ultimately, the raison d’etre of this book is that simple, humble impulse to record, as far as possible what it was like to live through such a period. I’m sure there are thousands, perhaps millions, of diaries and blogs and recordings all over the world with exactly the same motivation to memorialise.

For many it was the year that never happened, largely cut off from the quotidian pleasures, unable to travel or visit or see family, a year barely lived and best forgotten. But for others it was the year of nightmare, of horror, of grief, of loss and separation, a year that was as long as a century. Perhaps, it was also, for many people, a time of reconnecting with friends and family, of solidarity and learning, and for governments of rediscovering the value of the social as opposed to the market.

But for all of us, it was a time we never expected to experience, something our grandparents lived and talked about, a legend, almost a myth. We believed science had conquered nature, at least with regard to plagues; but Nature is not to be conquered, it holds in reserve a battalion or two ready to surprise us at any moment.

We have been prosecuting a scorched earth policy for at least 200 years, poisoning the planet, hollowing it out, choking it; it should be no surprise that our world has dealt us a blow in kind. A respiratory disease is the perfect metaphor for what we are doing to our habitat. Let’s hope we – and, more importantly, the great powers of capitalism and government – learn the lesson Nature has taught us with such severity.

Click here to be taken to the original Irish Times article

On Punctuation, Politics and Poetics - on the writing style of Smugglers

Recently a friend took me to task for not punctuating a poem of mine that he otherwise liked. He didn’t see the aesthetic or political argument for it, he told me, although, in declaring it ‘a fine poem’ he rather undermined the argument that it needed punctuation in the first place.

In this, first of two essays, I’d like to consider this absence of punctuation and in Part 2 I’ll turn my attention to the question of politics….

Click here to be taken to Part 1 of this essay.

Click here to be taken to Part 2